I wonder what it would take for "lowering emissions are required to grow the economy" to become the belief system the US was operating from?

A sudden Oil Co boycott of Citizens United

Or

Hell Freeze

You can install our site as a web app on your iOS device by utilizing the Add to Home Screen feature in Safari. Please see this thread for more details on this.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

I wonder what it would take for "lowering emissions are required to grow the economy" to become the belief system the US was operating from?

or cheaper EVs, solar panels, battery storage?A sudden Oil Co boycott of Citizens United

Or

Hell Freeze

Sacrificing solar and wind jobs to prop up dying coal jobs sure comes close to slowing the economy to emit more carbon.This is an interesting way to put things. Based on the US President's recent executive orders, it appears that the US is proceeding down the well understood general economic relationship that economic growth is dependent on increased emissions. Oops.

I wonder what it would take for "lowering emissions are required to grow the economy" to become the belief system the US was operating from?

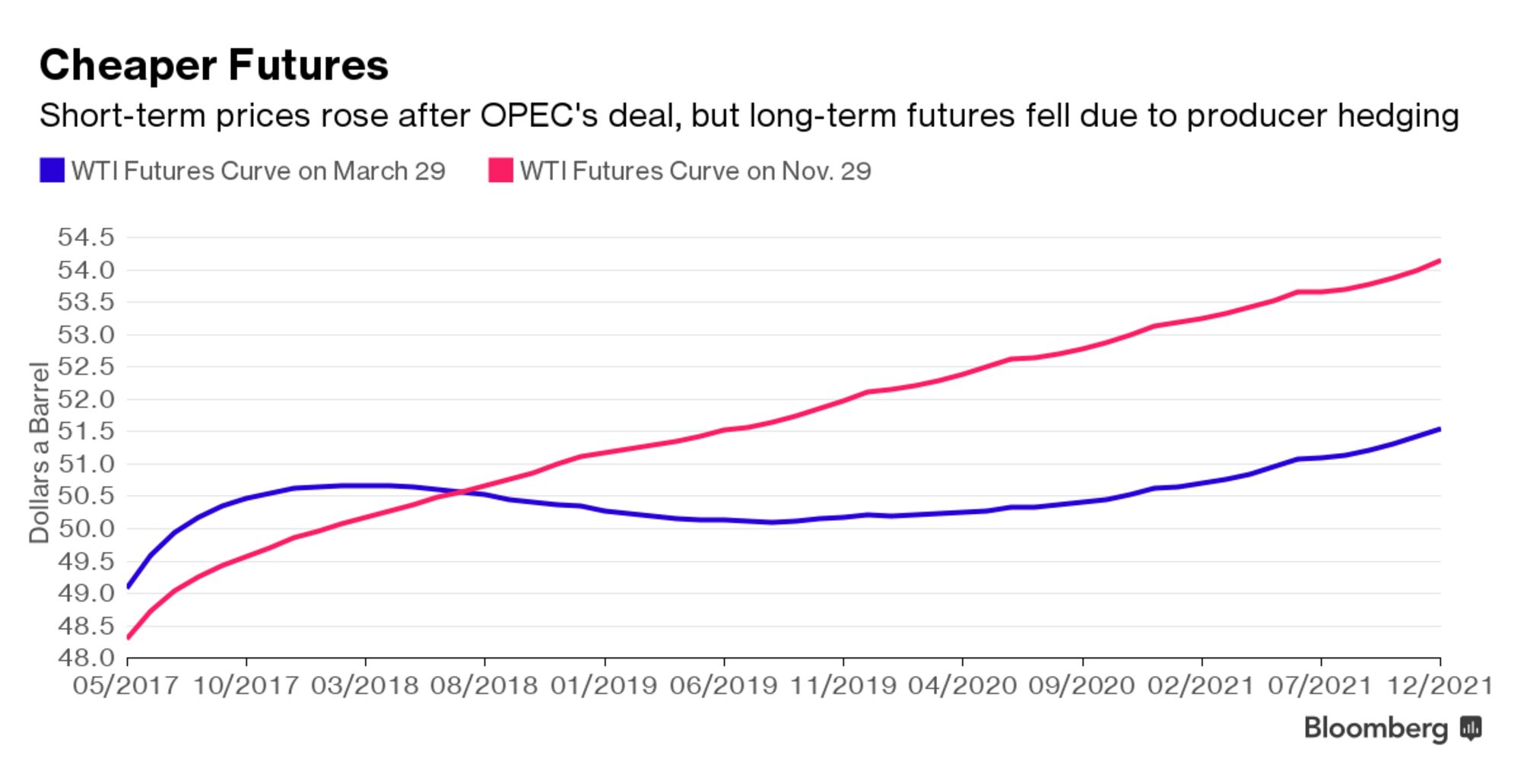

Good question. In general, I would suspect that it is hard to wait when you have debt to pay. But lease contract also may be a factor. Some producers needed to drill DUCs recently to keep their leases. It gives them a two year extension. So I suspect that beyond an extension, producers may need to actually complete some wells.Why wouldn't the DUC's will just sell further out, leveling prices out completely. It must be cheaper to store the oil in the ground then above.

SeekingAlpha said:Crude stockpiles are starting to decline in a sign that the production cuts implemented this year are bringing the market to balance, according to OPEC's Secretary-General Mohammad Barkindo.

"I remain cautiously optimistic that the market is already rebalancing," he told reporters in Baghdad.

Oil had its biggest weekly increase in 2017 last week, with futures advancing 5.5% to climb back above $50 a barrel.

Yeah, right. I'm not seeing all this rebalancing. US commercial crude stock has increased 12 weeks out of the last 13 weeks.Of course OPEC is going to say rebalancing is occurring.

Is the oil market rebalancing? - The United States Oil ETF, LP (NYSEARCA:USO) | Seeking Alpha

Of course OPEC is going to say rebalancing is occurring.

Is the oil market rebalancing? - The United States Oil ETF, LP (NYSEARCA:USO) | Seeking Alpha